Umbral

Title: Unveiling the Healing Power of Caribbean Folk Spiritism: Exploring Home Portals and Resistance in a Post-Colonial Context

As part of my research in preparation for the Artist Residency at the Berman Museum, I stumbled upon a captivating drawing of a "Hex" from the museum's collection (part of the PA Dutch tradition), which piqued my interest in exploring the realms of Caribbean healing practices, particularly folk spiritism. These practices have evolved over centuries as a response to the process of colonization, embodying a modest yet profound means of resistance. In this essay, I will delve into the significance of Caribbean folk spiritism, drawing connections to the development of home portals and its political context in the face of colonization.

Within the Caribbean, the rich tapestry of folk spiritism reflects a fusion of rituals and manifestations derived from diverse ethnic, racial, class, gender, and spiritual backgrounds. These practices have evolved into a distinct formula for survival, shaping a unique narrative of human transition. One aspect of this narrative lies in the role of "curanderxs" and other spiritual healers who serve as custodians of their communities, offering protection and guidance. Their rituals go beyond individual well-being, extending to the collective consciousness and creating a sense of solidarity among the people.

Caribbean folk spiritism intertwines elements of syncretism, blending indigenous beliefs, African traditions, and European influences. This syncretic nature serves as a testament to the complexity and adaptability of the Caribbean people, as they found ways to preserve their cultural heritage amidst the oppressive forces of colonization. The rituals and practices associated with folk spiritism act as a portal, enabling individuals and communities to transcend their immediate circumstances and envision a future filled with hope, strength, and collective empowerment.

Moreover, the development of home portals/thresholds/”umbrales,” within the context of Caribbean folk spiritism takes on profound political implications. Current waves of colonization bring not only physical displacement but also spiritual and cultural disconnection within the self and it future possibilities, to several extents it dislocates the self and collective imaginary and how it could help imagine aspects of reconstruction. In response, certain Caribbean communities have transformed their homes into sacred spaces, imbued with symbols, altars, and rituals that reinforce their sense of identity and resistance. Most important is also the sense that healers and visionaries such as folk mediums have allowed certain disruptions into concepts of time and space that have allowed people to protect their ways and evolvements amid colonization and its local political repercussions. These home portals serve as tangible expressions of sovereignty and self-determination, representing a reclaiming of their culture as a strategy of empowerment and an assertion of autonomy in the face of external control.

By exploring the interplay between Caribbean spiritism, home portals, and the political context of colonization, we can gain a deeper understanding of how these practices have shaped Caribbean identities and fostered a deep sense of solidarity as part of the strategies of survival and most important dissidence. The ability of healing traditions from curandrxs to heal and empower individuals and communities serves as a definer of Caribbean resistance against oppressive systems.

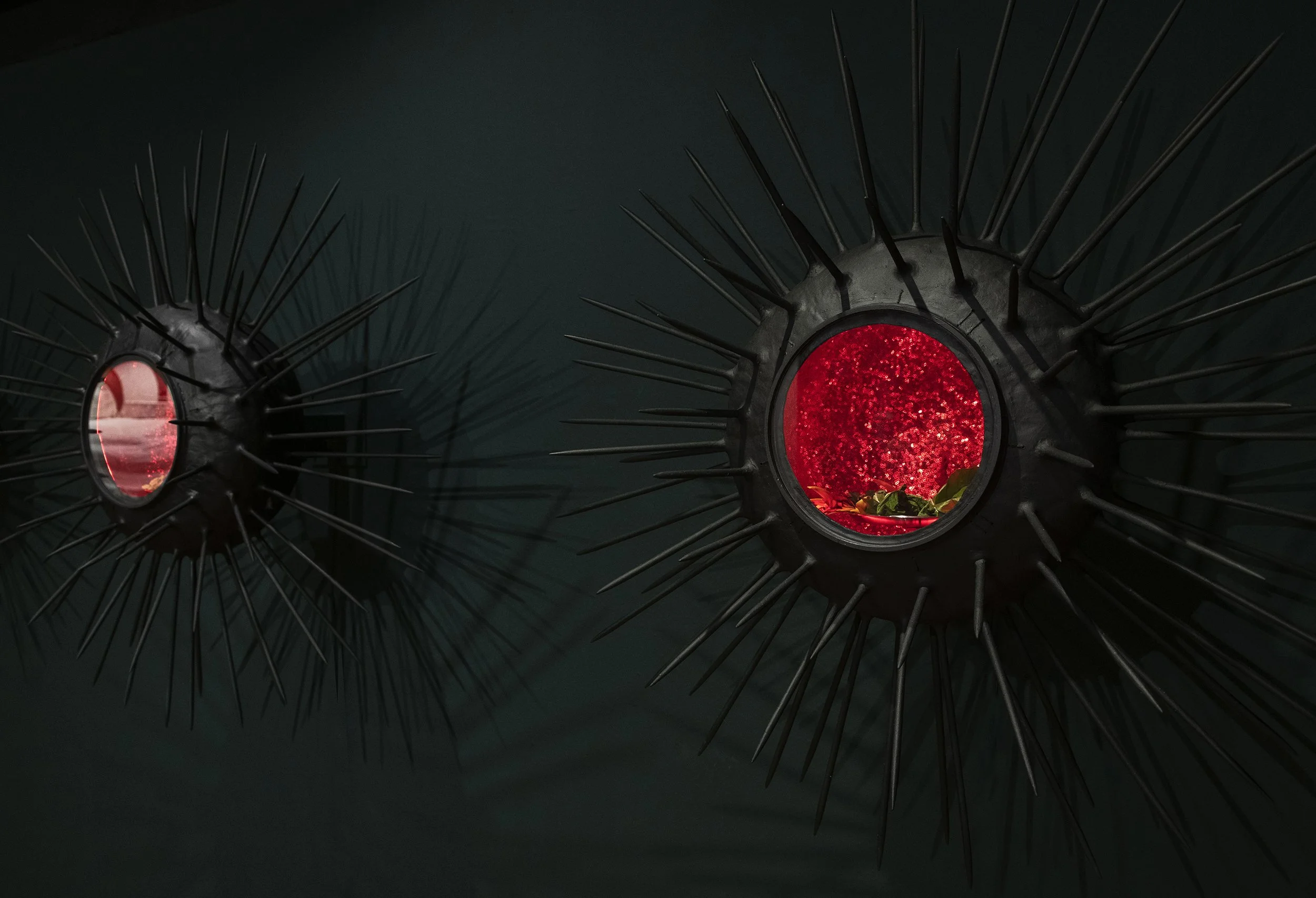

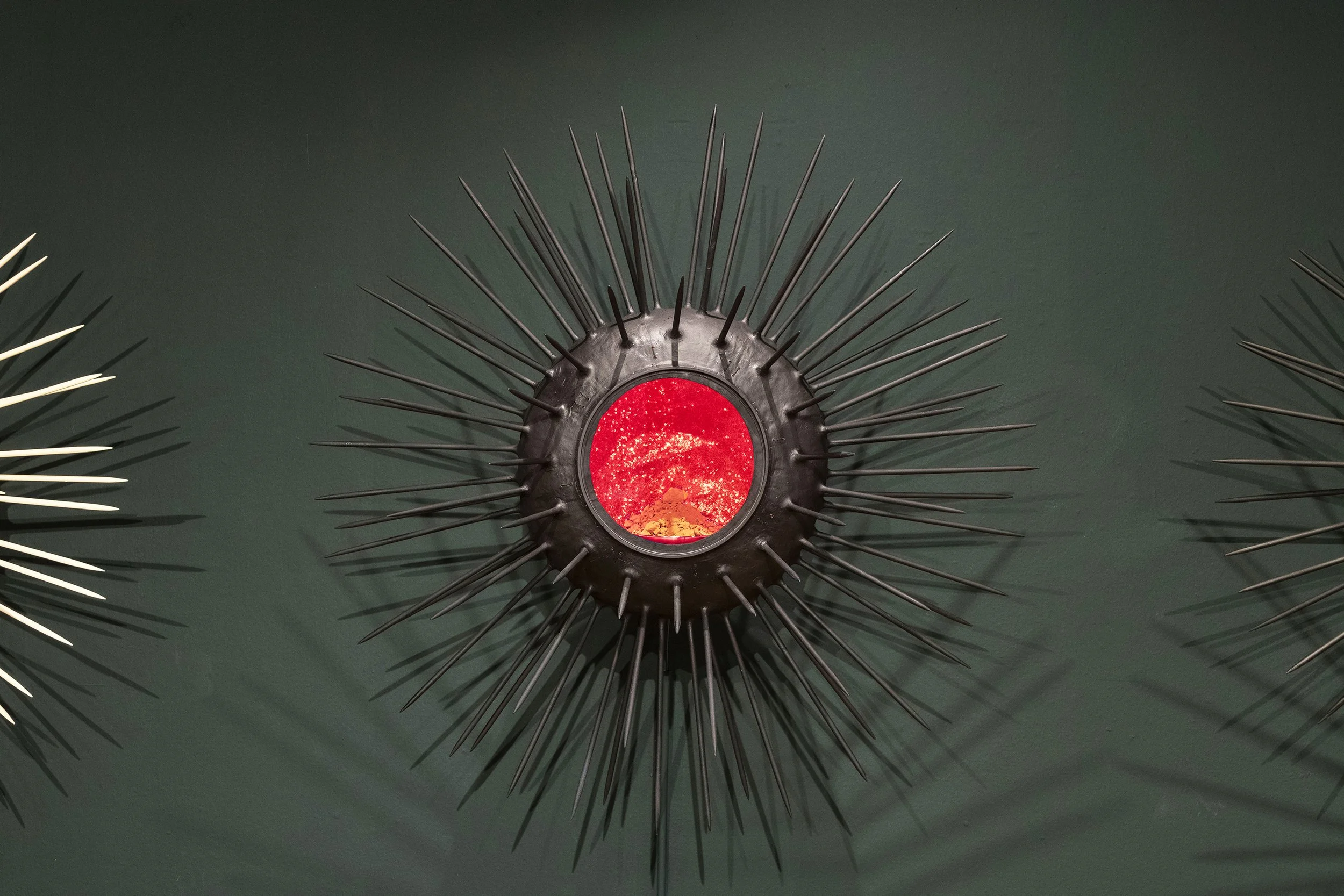

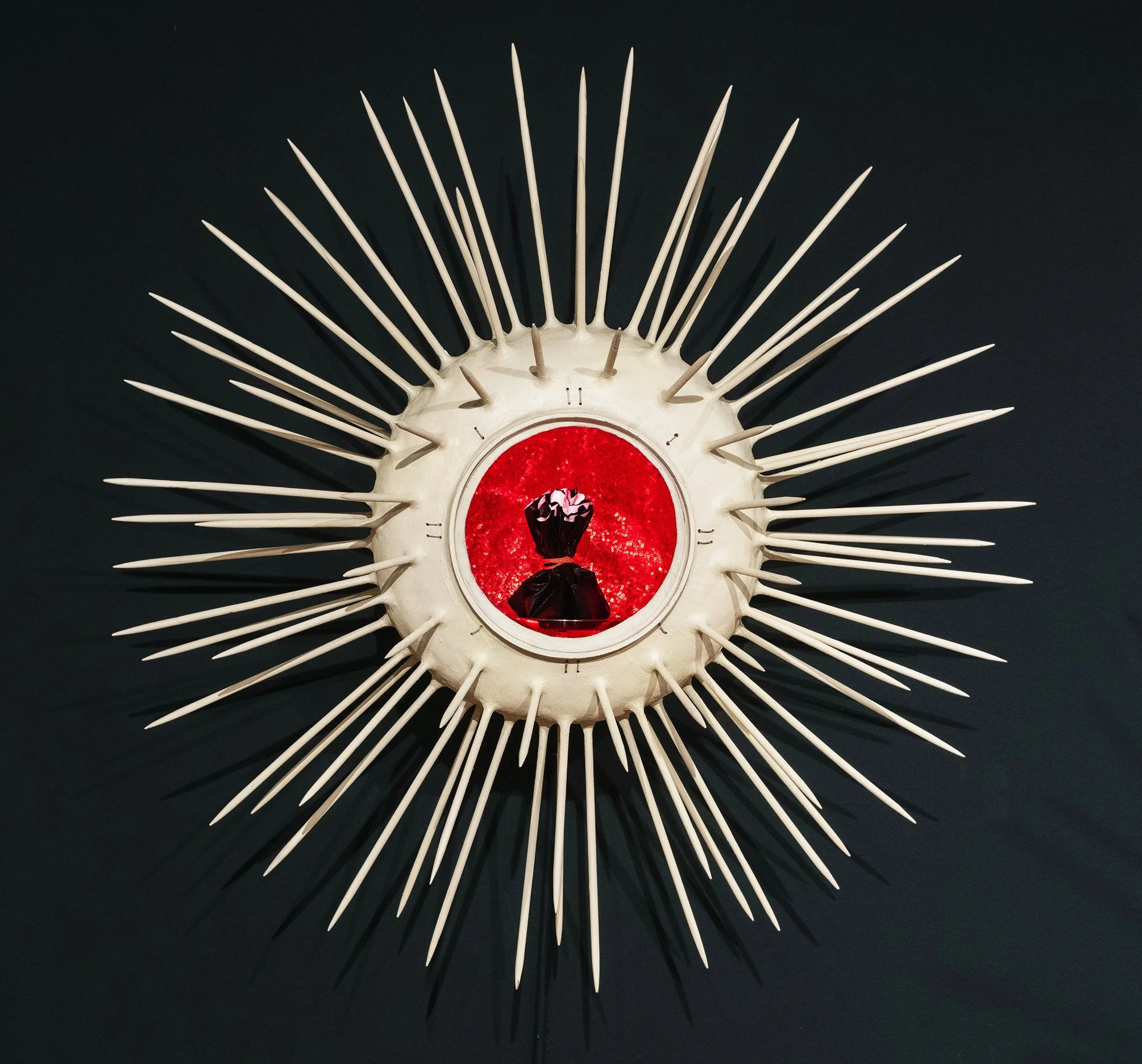

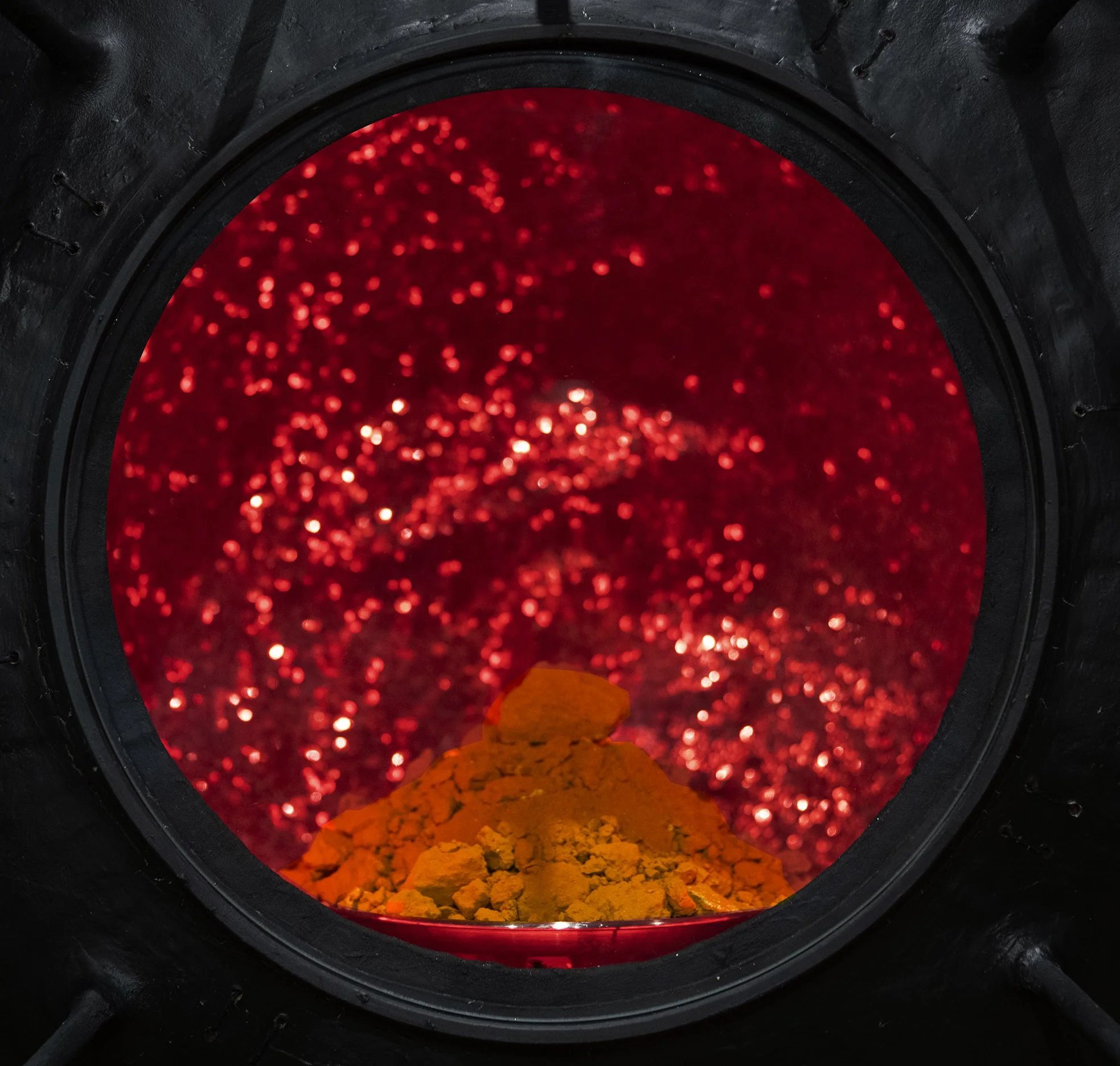

Barreras 1,2,3- 42x42 paper, fabric, glass, wood and folk medicine herbs, abandoned factory brick powder and storm water.

Egregoras mask (ritual garment for performance)

Barreras 1,2,3- 42x42 paper, fabric, glass, wood and folk medicine herbs, abandoned factory brick powder and storm water.

Barreras 1,2,3- 42x42 paper, fabric, glass, wood and folk medicine herbs, abandoned factory brick powder and storm water.

Atolón - 7'x4' woodcut on fabric

Barreras 1,2,3- 42x42 paper, fabric, glass, wood and folk medicine herbs, abandoned factory brick powder and storm water.

Altar

Installation view

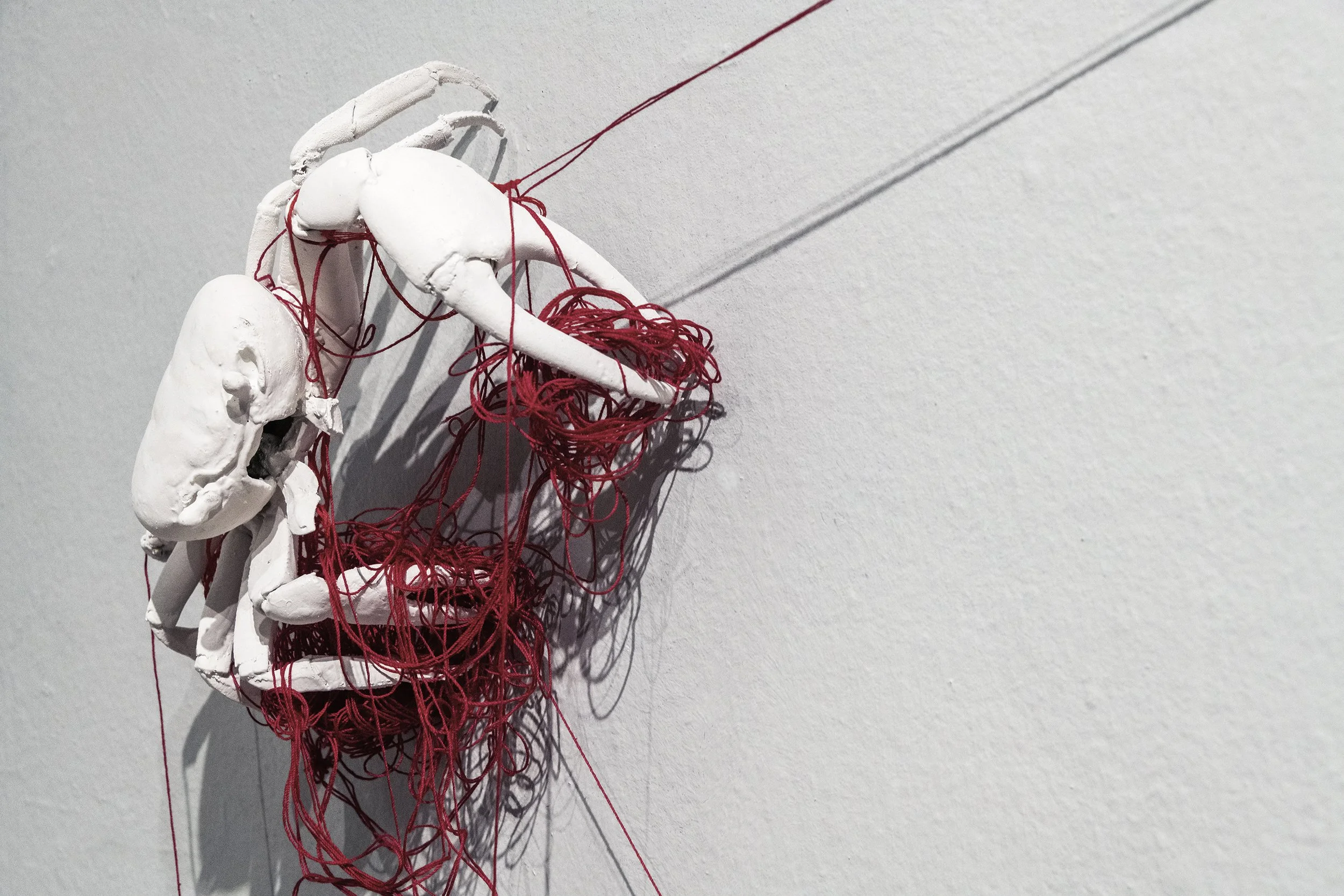

Cancer- crabs, paper and textiles

Cancer- crabs, paper and textiles

Egregoras (ceremonial suit for performance)

Installation view

Barreras (detail)

Atolón

By Selina Morales

How will we build a way forward? What power lives in, around, and because of our island? What everyday acts of resistance take shape in the hearts and minds of our people?

With these questions on his mind, José Ortiz-Pagán considers his hands and his know-how, as his grandmother taught him to, assembles an altar. Like many of us, he places fire and water on a tabletop in an act of hope and in an effort to communicate simultaneously with our ancestors and our oracles. Our past and our future. Drawing them into conversation, we pray for an answer to the crises we endure. Are these prayers simply hopes and dreams whispered into the wind, carried on the wings of butterflies until the weight of our future dissolves into the monte or the sea or a farther away landscape? I don’t believe so.

I believe, firstly, in these prayers as mechanisms for naming the world in which we want to live and that speaking them into the wind makes them so. Imagine these aspirations like little flames spreading around the island, alighting the waters, and catching out there in the diaspora. They feed the hard work of dreaming up new worlds, we keep our minds open to these prayers and expand them.

And, secondly, I believe in using old wisdom to make something new: carefully arranging photographs and candles on an altar to ask for a better future, using the palm of our hand to measure salt for habichuelas to nourish our movements, constructing paper maché horns of a vejigante mask to teach the next generation about the mechanisms we’ve used to survive. We hone our tools for change. The creative acts that make us Puerto Ricans hold power, communal power. And, this folk cultural knowledge holds paths to liberation.

My abuela is an espiritista healer - born in San Juan, and raised in Ponce. She left the island as a teen, returned as a grandmother, and left again seeking the company of relatives who felt they had no choice but to seek “prosperity” on the mainland. The magic and knowledge I have inherited from my abuela is my armor – my crisis management system. Her gifts have a role to play in making a future for Puerto Rico. After many years of observing José Ortiz-Pagán at work in our home city of Philadelphia, I can reflect on his use of inherited knowledge. Like me, he holds ancestral magic in his practice. He also carries forward a reverence and respect for possibilities held in nature and in the community. When we talk about these possibilities, he wonders out loud how they can be in service of collective liberation. How, for example, can we learn from the crab’s commitment to community, to join together to claim the future of our beloved island? We are in this together. How can we learn to move with intention and grace toward the future? Though our struggles are many, in the community we can choreograph a path forward.

Working in step with communities in Philadelphia, newcomers and long-time residents trust Ortiz-Pagán to hold and express their stories in his artwork. He is a gentle and thorough listener. He is a considerate community member who feels acute accountability to his neighbors. He’s been selected, again and again, as a visionary –one who can hold the truths of community and is given permission to interpret our lived experiences into the future. He lights little fires, whispers the change-making prayers, and does the work that community artists do.

With José Ortiz-Pagán’s Atolón we find a space to contemplate the notion of hope. It offers spiritual, natural and culturally enriched interventions sourced from everyday acts- sewing, praying, swimming, mapping, sacrificing, mechanizing, migrating, and coping. Each artwork in this atoll is multi-layered, taken for their beauty alone ignores the critical message that our everyday experiences as Puerto Ricans – on the island or in the diaspora – are ingredients for recipes to get free.

Atolón is also a space to contemplate action. What tools lay at our fingertips – and how will we use them? What resources swim in our oceans – what magic can we learn from them? From where will we draw out power – and what will we do with it once we learn to wield it? I believe it is the vision of artists that will help us find the path.

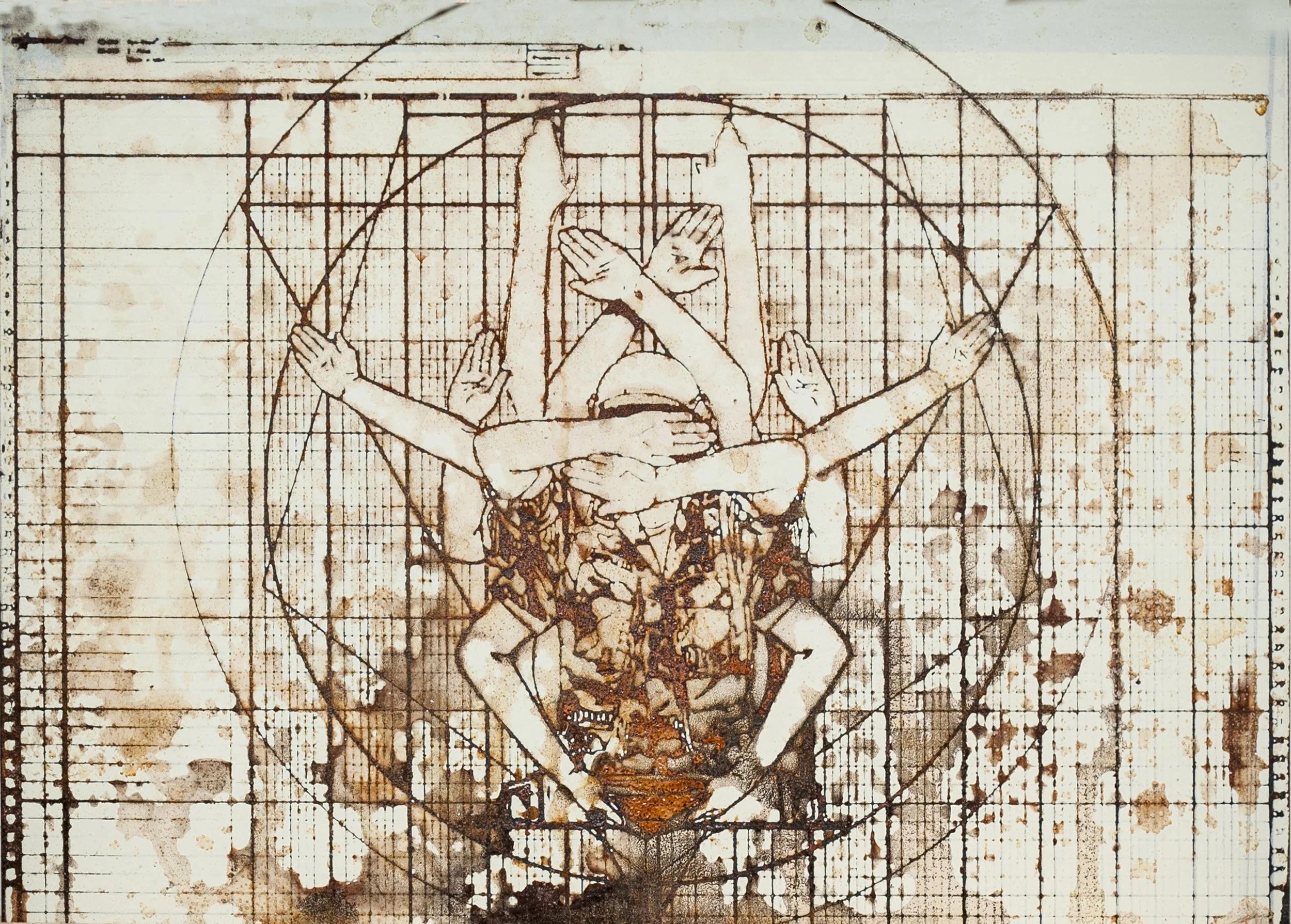

48x48 Stencil on steel slab

48x48 Stencil on steel slab

48x48 Stencil on steel slab

48x48 Stencil on steel slab

Installation view

12x18 on steel plate

12x18 on steel plate

Cenít

The exhibition Cenít developed a body of work that deals with geographies and astronomy as a way to map the two tragic and historic political schemes within Latin America. In particular, the work approaches two distinct cases in which the bodies of students were violently desecrated in order for US-backed governments to send political messages.

The work itself brings coordinates of specific places on which these historic events happened and connects them with a larger sense of repercussions via the use of constellations that mark the specific time at which such crimes happened. The use of rust and metal appeals to the use of violence in the context of industrialized society as well as speaks about the societal wounds that these events inflicted in the evolvement of the socio-political imaginary of two countries, Mexico and Puerto Rico. The series is a commentary on the assassination of 43 students in Mexico in 2014 (Ayotzinapa), which in many similar ways parallels the history of two students (Carlos Enrique Soto-Arriví and Arnaldo Darío Rosado-Torres), assassinated in Puerto Rico back in 1978 (Cerro Maravilla).